In 1619, under the patronage of King James I and his son Charles, the Prince of Wales, a tapestry workshop was established in Mortlake, London. Unfortunately, it was short-lived, closing in 1703, but many of the tapestries made in Mortlake still adorn the walls of palaces and country houses across Britain. Large pictorial tapestries proved popular among the rich and royal, particularly from the 14th century onward. When the Mortlake tapestry workshop flourished, it created renowned series including The Story of Abraham and the Story of Hero and Leander. After years of pollution, light exposure, and prolonged periods of hanging on walls, varying levels of deterioration occurred. Focusing primarily on the conservation of tapestries, I discuss the debates surrounding the restoration of historic buildings, re-lining of paintings, and light pollution, to provide a broader understanding of conservation. I also note the advances made in conservation since the 1960s, whilst touching on art historian Cesare Brandi’s Theory of Restoration, as it provides advisory guidelines for conserving art. The late 20th century saw the emergence of conservation turn into a professional discipline, with clearer distinctions being made within this line of work. Furthermore, I will explore acts of conservation that have been carried out on tapestries in a wider field, before specifically focusing the ones manufactured at Mortlake. The Mortlake tapestries discussed are part of the National Trust and Historic Royal Palaces collections. A portion of this dissertation will investigate the techniques practiced by these institutions in their conservation studios, and their advances in this field.

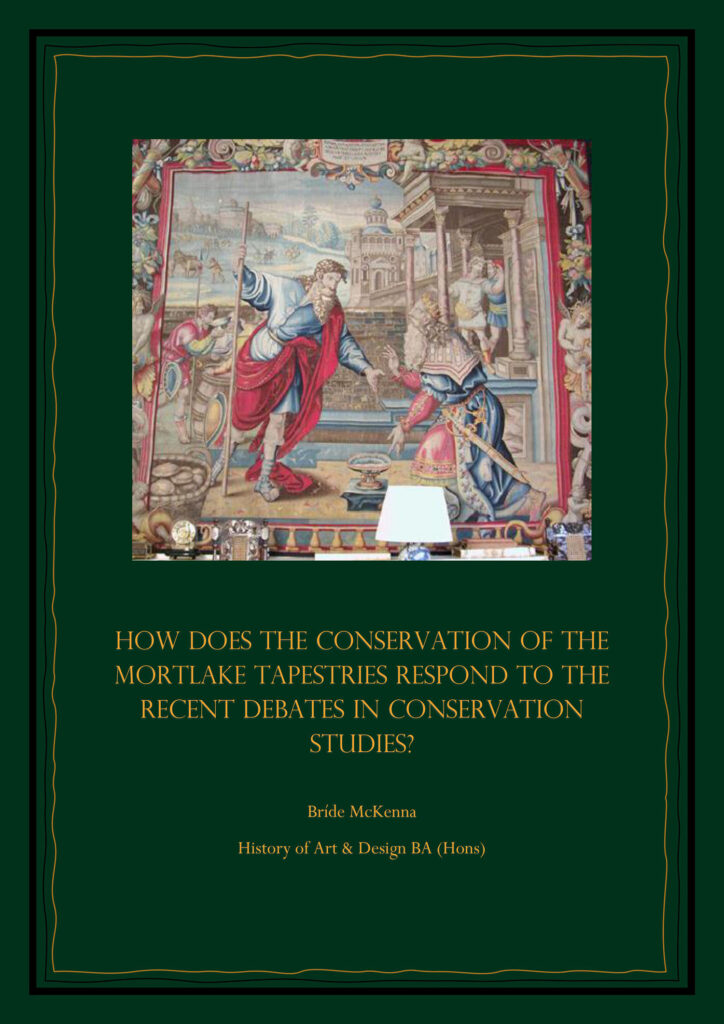

Mortlake Tapestry Workshop. February. 1623. Woven silk, wool, gilt metal, and silver wrapped thread. 3.98 x 3.47 m. Kensington Palace. Royal Collection Trust.